How Bright Is the Sun on Other Planets?

How strong is the Sun on Mars? How much sunlight reaches Saturn or Neptune? Scientists rely on a powerful mathematical formula to find out.

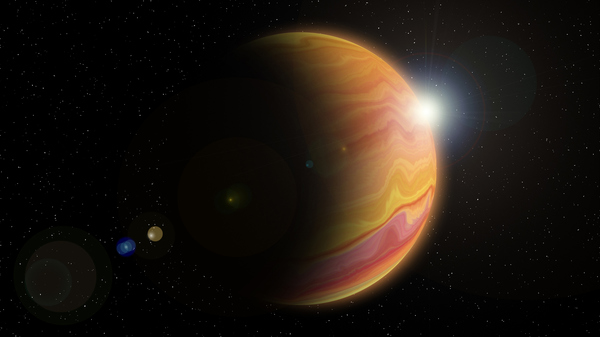

Jupiter gets just a small fraction of the sunlight we receive on Earth.

©iStockphoto.com/suman bahaunik

A Blazing Sky and a Distant Glow

To discover how much sunlight reaches other planets, astronomers rely on an equation called the Inverse Square Law. The title may sound a bit daunting, but the key to understanding this formula is relatively simple: it measures cosmic distances in astronomical units (AU), with 1 AU being the average distance from the Sun to Earth.

So we know Mercury is roughly three times closer to the Sun than Earth is, at 0.387 AU. The Inverse Square Law lets us calculate that Mercury gets 668%, or more than six times the amount of the sunlight that hits our home planet. (See “Crunching the Numbers” to learn how the math works).

Mars orbits at an average distance of 1.5 AU from the Sun. The math behind the law shows that the red planet gets 44%, or less than half the sunlight that reaches Earth.

Sailing deeper into space, we encounter the mighty gas giant Jupiter at 5.2 AU, so we are able to calculate that Jupiter experiences around 3.7% of the light that reaches Earth, a weak Sun indeed.

Farthest out, frigid Neptune is located at 30 AU, meaning it gets only the faintest glimmer of sunlight, just a fraction of a percent - a total of 0.1% of our light.

Different on the Surface?

The Inverse Square Law tells us how much sunlight reaches the location of the planet, but what if you were actually standing on the surface? How much Sun would come through? Wouldn't clouds, dust, and gas have a lot to say?

The answer to that is yes.

On Mercury, for example, there is no atmosphere to impair the Sun´s rays, only a thin layer called an exosphere, so on the surface you would experience powerful Sun, open skies and intense heat with temperatures up to 430 degrees celsius (800 Fahrenheit).

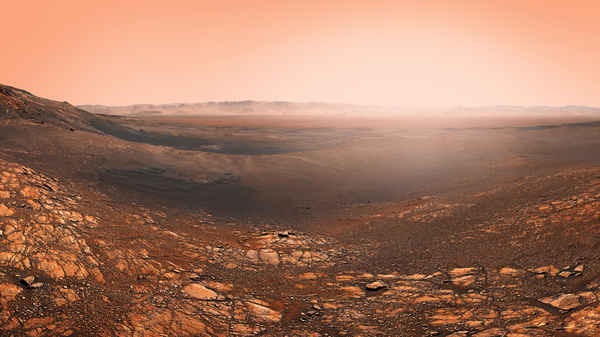

Mars has a thin atmosphere, so the sky there has a hazy, reddish look from the surface. Dust in the sky would block some of the sunlight, with winds whipping up massive dust storms that can take months to settle to the surface again.

As a gas giant, Saturn has no real surface to stand on, and unrelenting pressure would destroy your spacecraft as you descended towards its center. But if you could get there, you would encounter massive clouds of gray, brown, and yellow gasses limiting the sunlight.

Neptune also has no solid surface, but hosts a mixture of water and different kinds of ice over a solid core. In the atmosphere, you would encounter hydrogen, helium, and frozen methane clouds filling the skies that would block the dim rays of the distant Sun.

Martian skies are often clouded by dust storms, blocking some of the sunlight.

©iStockphoto.com/24K-Production

Why Mars has more leap years than Earth

Crunching the Numbers

The Inverse Square Law formula itself (1/d^2, where d = distance of Earth to Sun) may seem complicated, but by simplifying the average distance between the Sun and Earth (149,587,871 kilometers or 92,955,807 miles) as 1 unit of AU,the math becomes much easier.

Let's take Earth as an example. We know that d(the average distance) from the Sun to Earth is 1 AU, so the formula becomes 1/1^2 = 1.

The result means that Earth is 1 AU from the Sun and receives an amount of light we call 1 unit of total solar irradiance. So when we apply the math to locations that calculate out to a number greater than 1,we know they receive moresunlight than Earth, while those that are below 1 receive less than our planet.

Fortunately, we already know the average distance of the Sun to the other planets in our solar system in AU:

Mercury 0.387 (roughly 3 times closer to the Sun than Earth is)

Venus 0.723

Earth 1.000

Mars 1.523

Jupiter 5.202

Saturn 9.538

Uranus 19.181

Neptune 30.057 (roughly 30 times farther away from the Sun than Earth is)

Figuring out how much sunlight reaches these positions then becomes a question of applying the math. The numbers for Mars would read: 1/d^2 = 1/1.5^2 = 1/2.25 = 44%.

For Jupiter, the calculation looks like this: 1/d^2 = 1/5.2^2 = 1/27 = 3.7%.

And forNeptune:1/d^2 = 1/30^2 = 1/900 -0.1%